The last few years have been ones of what seems like fast-paced change. covid? Come and gone. Politics? In turmoil. The worldwide economy? Bouncing around like a pinball machine. And in keeping with other world events, we have noticed some changes in how people find, buy, and sell pens as well. These changes, sadly, have had a major impact on how vintage pen repair can work.

Boring History

When we started to be involved in pen sales and repair, about 15 years ago, finding pens was pretty easy. If you went to an antique show or mall, you could come out with a half dozen or more good-quality pens in hand, often for $20-50 each. Sure, they needed to be cleaned and have the filling system repaired, but they were always there.

Additionally, ebay was established as a good source of pens, although costs would be higher due to shipping. But, again, good wares were to be had, with a bit of patience. Pen shows were starting up everywhere across North America, and you could find tables covered with pens, new and old. And you could often negotiate a good price, especially as you got to know various vendors and collectors.

However, with social media came the drive to make a profit, often driven by special interests. Forums started to make people more aware of pricing, and many hobbyists became business-people. And newly interested people of all ages swarmed in, as they discovered they could start a self-funding hobby without much effort.

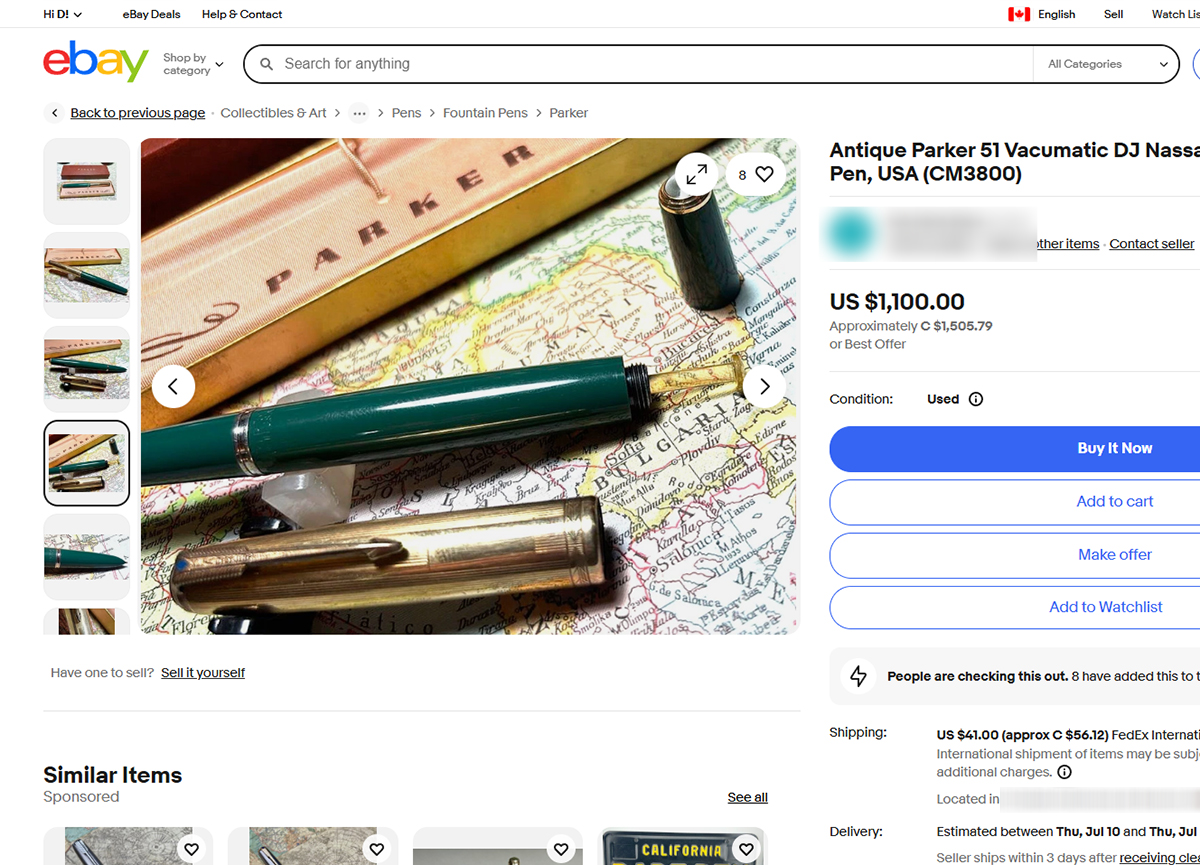

Around this time, there were reports of swarms of visor-toting young men descending on pen shows to clear out all the Parker 51s. Inflated ebay prices meant that antique dealers started to ask $200 for a broken pen, rather than $30. But ebay had changed from an auction site for pens to to one dominated by ‘buy it now’ listings, with higher and higher prices sitting for longer and longer periods of time.

covid hit, and home confinement turbocharged the process of changing hobbyists in to internet-based money makers. Then inflation skyrocketed, so the price of everything went up, and up, and up.

Where Are We Now?

By now things are a bit different. Well, a lot different.

When we recently attended the biggest outdoor antique show in Canada, we found one pen. (A nice Parker 51.) We could have bought a second pen, but demand for that brand is far lower, so the price didn’t work. But, to be fair, it was there. Several hundred vendors, thousands of attendees, and no pens.

We don’t find pens in antique malls any more, other than possibly, occasionally, a single sad, very broken third-tier-manufacturer one. Not even good pens for parts. Just an empty pen desert.

In the new pen world, there are loads of inexpensive ‘starter’ pen brands. And there are many, many (expensive) boutique ink makers. But Waterman’s Canada stopped selling bottled ink, for the first time in over 100 years.

In the vintage pen world, no one is making parts for anything, with few exceptions. There are a very few people making latex sacs and specialty washers. (By “few”, I mean count-them-on-one-hand few.) And generic pressure bars that fit most (but not all) pens. But not feeds, caps, cap rings, clips, nibs, buttons, or piston parts. These need a skilled hand, and are made in batches of one or two, on-demand if at all.

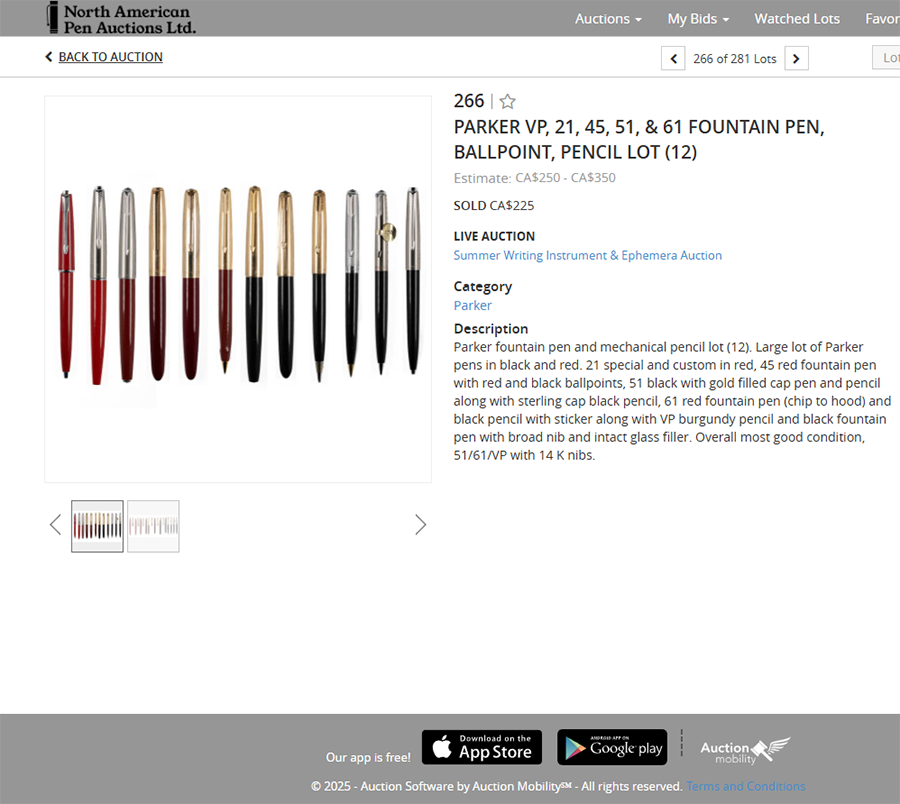

On the bright side, a dedicated pen auction house has opened up (North American Pen Auctions). In the interests of full disclosure, it is run by a friend and colleague of mine here in Toronto. It has been very successful, and that has shed some light on some of the impacts of these other changes, and where things are headed.

There is another side to the auction house development, though. A solid supply of pens “in the wild” has always come from estate sales. Antique ‘pickers’ used to line up at dawn, then muscle their way through estate sales, picking up anything that seemed of value, often by the box-load. These items would be channeled to ebay, antique mall booths, and flea markets. Because these ‘pickers’ knew little of specific values, you could find a pen for $20, that the ‘picker’ had bought for $1.

There are an increasing number of online auction services that target the estate sale market. Now, items are listed without an open house, and they are offered instantly around the world. Anyone browsing these listings is rubbing shoulders with folks with specific interests and far better ideas of current values. And so estate sales have ceased to be a meaningful source of lower-cost pens, or parts pens.

What Defines Value?

Everyone is familiar with the old axiom “collect what you love!” But few know the other half of the statement: “because anything you buy, regardless of price, will be devalued by 90% as soon as you take possession of it. So love is really the only payback.” No, really, that is actually a truth known by investment professionals, and never admitted by collectors or retailers of anything.

Traditionally, vintage pen collectors have been mostly of a certain demographic: older (cough, cough, boomers, cough), paler, and wealthier. Often from among the ranks of professionals, they were able to travel to pen shows, and well-heeled enough to buy whatever struck their fancy.

We have been shown collections of hundreds of Parker prototypes, multiple portfolios of full-overlay Conklins (the stars are pretty), and boxes upon boxes of unopened Montblanc ‘Limited Editions’, all held by folks meeting this description. And everyone has a few boxes of by-blows: broken parts pens, of various brands. Sometimes there are hoards of new-old-stock parts from Ye Olden Times of Janesville (Parker) or Fort Madison (Sheaffer’s). And these collections all have one thing in common: the owners have a definite opinion of their value.

Say, for example, you have collected pens for years. You grew a network of friends, colleagues, and events related to this interest. You slowly grew your knowledge, and curated an excellent collection of your favourite pens. You kept to makers of what you considered the best quality. And you found some great underpriced treasures, as well as a few that you just had to have, regardless of cost. You justified it, if not to yourself to your loved ones, by explaining that these are also, in fact, a “good investment”. And this just makes sense. They aren’t making the goods anymore (low supply). And more and more people are interested in collecting them (high demand). Everyone knows about supply and demand, right?

When Supply & Demand Get Fuzzy

To be fair, this could describe many collectors: art, vintage tools, classic cars. But the one thing that all collectors have also done is collect pricing information. This formerly came from physical price guides. Then it transmorphed into ebay listings. Then auction houses started saving all ‘prices realized’, no matter how minor the item (as a way of attracting traffic to their sites. A “value-added” approach.) And because the internet has allowed everyone to compare notes, it has ended up being the largest price collusion exercise in history.

And this begs an anecdote.

An Anecdote:

Just before the internet (yes, that long ago), we tried bookselling. First editions, although this was realistically just whatever we could scout out that was underpriced. And, being pre-internet, this meant memorizing authors, titles, and ways of designating editions. It also meant finding customers, in our case booksellers with a physical shop (remember bookshops?)

We got to know one crusty older fellow in Toronto’s bookseller’s row. And one day he confided that he had been consulted by the authors of The Authoritative price guide for rare books, specifically because of his intimacy with Canadian literature.

Now, he absolutely did know his prices on CanLit. And every one he submitted was soundly rejected. Why? The reasoning went: ‘Our price guide gets re-issued every seven to ten years. Therefore, you must provide the highest possible price, in the most exclusive market, and then index it to speculated inflation for ten years from now. That is the price we will put in our book.’

Using this formula, his estimate of $75 for a first edition copy of “The Handmaid’s Tale” would become:

- $100 (because it might be signed),

- $150 (because it might be sold in New York’s Antiquarian Book Fair), and then,

- $200 (guessing 5% inflation over ten years, then rounding up because we like easy-to-remember numbers.)

To his credit, he couldn’t stomach the whole thing and walked away from the authors, and some easy money & prestige. I always liked him.

(As a summary note to this anecdote, five years later books started to be listed online. Everyone realized that many “rare” books were actually quite common. Prices crashed due to huge supply, and many bookshops went out of business.) Our crusty old friend just retired.

The point is this: When humans are involved, things always get messy. It’s always humans who are buying and collecting things, and there is nothing prone to messy like deciding the value of what you have sitting around you. So, those ebay prices? “Buy It Now”s that were never sold. The auction values? The only two guys who wanted it were there that day. The price guide? Well, see our anecdote above for that one.

“Cognitive dissonance” is a phrase describing the conflict in your head when your reality hits hard into actual reality. And people often will deny actual reality, as a means of not going crazy. This may not make much sense, until you are faced with cognitive dissonance yourself.

A thing that no one ever, ever wants to talk about (read: block out of existence) is the cost of finding a buyer. For one pen, let alone a thousand. It can take years to disperse a collection. And most of the interested people already have a collection already. Young people don’t have a job, let alone a career with disposable income. Or a house, for that matter. The foreign market? There is no foreign market, just the big ol’ internet, that everyone in the whole wide world buys from.

Another let’s-agree-not-to-think-about-it factor is that everyone wants a cut of the preconceived profit: the collector themself; their family; the auctioneer or retail shop; and the buyer (so they can re-sell and use the profits for their actual pen interests.) Multiply this by every single pen. If they move in “lots”, to use auction parlance, they go for lower prices, which then get accordingly diluted.

A good auction house can provide a reasonable solution, though. A collector can consign pens in quantity to a person who knows pens like they do. For a reasonable percentage the auction can market globally, and you get an e-deposit a few weeks later. And this sort of auction is what gets hoards (supply) moving again. Although prices are higher than pens found ‘in the wild’ (ie: antique shops and estate sales), they are at least available. And the collector will realize about 40-60% of what they have invested. (-60% investment, anyone? Going once…going twice…) But auctioning is easy, and fast, and these two factors convince many people.

All of these factors, and more, make the simple supply & demand equation fall right over in a heap. And that means that years of collecting, and all the money spent on it, is not actually invested. It is mostly just spent.

How Finding Parts Works

With a lack of “in the wild” pens, we are increasingly relying on auctions. Because parts pens at auction get sold in “lots” of multiples, it means that someone looking for a single part for a single customer’s pen must buy five or ten pens to get it. And that’s not always realistic.

As an example, a lot of five non-functional Parker 51s might sell for $200 on a great day (plus buyer’s premium, plus shipping. Call it $250?) If all you need is that cedar blue demi-sized hood, you then have to carry the other $210 of cost for five years, until you use all the parts. And if it is a not-as-desireable-as-a-51 pen like, say, an Eclipse, you will be carrying $140 for ten years. Times the number of pens you are looking for at any given time. That could work out like this:

- three customers this month needing a part you don’t have, times

- $150-250 for a parts lot at auction, less the $20-50 you can charge immediately for the part, times

- 12 months in a year, equals

- $1500-$2400 of parts, per year, held indefinitely.

You also have to factor in storage space for those parts, and time to clean and process and organize them. If you are in business for ten years, that is an investment of $15,000-$24,000, just for parts. Is $15,000 a good investment if it is for something that might never sell, takes up space, and needs insurance?

So what is the point of all this whining?

Finally! What Does This Have To Do With Parts Pens?

Parts pens inhabit a funny corner of pen collecting. They are the pens that need so much repair that their value as a whole, functioning pen is compromised. Like the Waterman red ripple with the broken lever box: $250 in repairs, plus $75 purchase price, for a pen worth $250, or less? It just doesn’t make sense. Unless you are a repair person.

A pen mechanic will see a clean cap with a good clip ($50), a viable nib ($100), a solid barrel ($40), a pressure bar inside ($15), and a section and feed ($25). A $75 pen yields over $200 of usable parts, and you might just have a spare lever box in the bin, too.

But what if someone imagines that one day this broken pen will be worth $500? Or what if they just read about fabulous Waterman flexy nibs (and don’t have enough experience to know this one is semi-flex) and will use it as a dip pen, for funsies and Instagram hits? Or what if they imagine they will one day repair pens and want this as a learning experience?

And this is the tough situation we are in now. There are many pen hoards held by older folks who want to make what they perceive as a good profit, or else they will just sit on them. Which means they sit on them for a long, long time, because the perceived profit is unrealistic, and hope springs eternal.

And there are many new collectors who want to amass the sort of hoard that was once available, and have a share in the perceived profits, but can’t find the pens. So when they do find a pen, it is second- or third-rate, but they snap it up, and treasure it anyways. (To be fair, who is anyone to diss someone’s treasure, however it compares?)

And there are some folks who will buy pens, then just send them to the repair person who is then expected to spend hours sourcing parts, and then make them whole, no matter how busted they are. (Not kidding. We recently had a Parker 61 where the only part viable on the pen was the nib. They were adamant in wanting it “repaired”, and wanted all the old parts back. We tried, but ended up sending it back. And no, there was no sentimental value, just a pen they had bought.)

And this various new version of demand, coupled with artificial scarcity (remember hoards?), means that when we go looking for parts, there is just a desert. Which, in turn, means that our prices have to go up drastically. Not just because the parts we do have are increasingly dear, although there is that. But also because it can take hours of online effort, for months or years, to find a part that once might have been a phone call away. Or a trip to the antique mall. Or just a stroll over to the parts bin.

On, Into the Future

Does this mean that pens are a write-off? (Groan. Sorry.) By no means! Pens are great. We love pens. And we love repairing pens.

But it does mean that there are almost no remaining bargains in vintage pens. It is a hobby for the comfortably well-off; it is a hobby for those who love pens. And not an investment, but a labour of love.

It also means that the cost of repairs is up, across the board of repair people. And–we haven’t touched on this–the board is growing smaller as time goes on. We have finally risen our prices to be on par with our colleagues in the US; only the second time for a rise in 15 years. And defraying the cost of parts searches is part of that.

However, we still treasure the times that we can restore a family pen to functionality. Or the odd time that a pristine pen, at a venerable 80 or 100 years old, comes across our bench.

And there are a number of young people who have found, or inherited, great pens. And those pens sometimes take only a little to restore. And they are fully appreciated by their owners. In fact, a collection of five hard-won pens is likely more appreciated than a collection of 1,000 rarities bought with ease. And it is a joy to support and advise these newcomers. To occasionally dispel some confused ‘received wisdom’. And to see them sail into life with a solid appreciation for a solid and well-designed and beautiful pen.

It makes up for a lot of frustration at things you just can’t do anything about. Doing something you can do something about.